Check out these precision grinding services images:

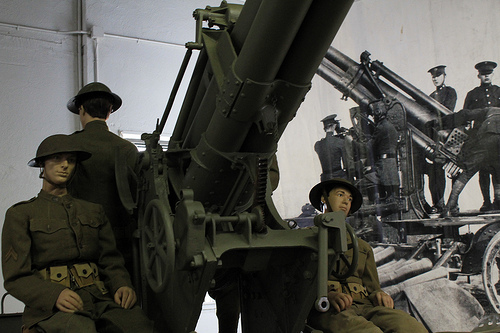

M1918 3-Inch Anti-Aircraft Gun

Image by Fidgit the Time Bandit

One display reads:

“The purpose of anti-aviation defense is to protect our own forces and establishments from hostile attack and observation from the air by keeping enemy aeroplanes at a distance.” – Brigadier General James A. Shipton, 1917

When the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, we lagged far behind most nations in adopting Air Defense methods. Thrust into a conflict where new technologies like machine guns, chemical weaponry, tanks and airplanes had completely revolutionized warfare, the American Expeditionary Force was forced to modernize and adapt quickly.

On 26 July 1917, Brigadier General James Shipton and Captains Glenn Anderson and George Humbert left the United States with the first contingent of American combat troops destined for the Western Front. The three officers were tasked with observing both British and French anti-aircraft methods and establishing a new American Anti-Aircraft Service. While General Shipton coordinated with the British and French to acquire the necessary equipment for American air defense, Anderson and Humbert took the lead on researching Allied techniques. The two captains quickly determined that the French methods were far more effective. As a result, both attended the French Anti-aircraft school at Arnouville-les-Gonesse and upon completion established a co-located American school to instruct incoming American anti-aircraft officers and enlisted on the new doctrine.

Anderson and Humbert incorporated some effective British techniques, which resulted in the use of searchlights for locating enemy aircraft at night. Searchlights, coupled with acoustic locators like the French used allowed for better target acquisition and therefore better accuracy for both the heavy caliber and machine guns on target. The first American anti-aircraft class began in September 1917 and consisted of twenty-five officers.

The school was divided into two sections, focused on employing artillery and machine guns in the antiaircraft role. A third section, focused on searchlights, was created in January 1918. During its existence, the American Anti-aircraft school at Arnouville trained 578 officers and 12,000 enlisted in the employment of anti-aircraft systems of the day.

Using a mix of heavy guns, machine guns, sound locators and searchlights, American anti-aircraft units were able to better defend Allied positions and as a result, better engage enemy aircraft. By the time the Armistice ended World War I on November 11th 1918, the American Anti-aircraft Service had gone from an untested, cobbled-together organization to the most successful air defense arm in the world.

The next display reads:

WWI – Anti-Aircraft Machine Gun Battalions

With the establishment of the American Anti-aircraft School at Arnouville-les-Gonesse in October of 1917, the American Expeditionary Force had its own training program for anti-aircraft gunnery in Europe. The school trained US servicemen on the use of heavy guns, machine guns and searchlights. Five anti-aircraft batteries (75mm) and seven anti-aircraft machine gun battalions were activated during World War I. Of those seven machine gun battalions, only the 1st and 2nd Battalions saw combat; the remaining five battalions were either in training or in transit to Europe by the cessation of hostilities.

While the heavy gun batteries were focused on deterring enemy overflights of friendly territory, the machine gun battalions were tasked with directly engaging enemy aircraft. During their brief existence, the 1st and 2nd AA Machine Gun Battalions established a new standard for Allied anti-aircraft machine gun units. Firing just over 225,000 rounds of .30 caliber ammunition, the two battalions shot down 41 German airplanes; or one enemy airplane per 5,500 rounds. Allied statistics could only account for two enemy aircraft per 200,000 rounds by the end of World War I.

The official US kill tally by the end of the war stood at 58 confirmed airplanes shot down by both heavy guns and machine gun units. However, this fairly small number does not accurately reflect the performance of US anti-aircraft units. That figure did not include aircraft downed by American anti-aircraft troops serving on foreign equipment or with foreign units, where credit for the kill went to the higher Allied nation headquarters. Therefore, on 18 May 1918, while serving under the French Army, the 2nd Anti-aircraft Battery was not given credit for a kill, even though the unit shot down the US Anti-aircraft Service’s first airplane.

Despite the flawed kill confirmation process, the anti-aircraft machine gun battalions performed admirably both in the anti-aircraft and ground support roles, setting the standard of tactical flexibility that continues as a cornerstone of the Air Defense Artillery branch of the 21st Century.

Use of improvised anti-aircraft mounts were, like tree stumps, included in the AA machine gun training program.

The French Hotchkiss machine gun was one of the standard anti-aircraft weapons used by US forces on the Western Front.

Anti-aircraft machine guns became a necessity as World War I dragged on and aerial attacks on ground forces increased.

Acoustic locators enabled anti-aircraft units to detect inbound aircraft at greater distances, thereby giving gunners more time to bring their guns to bear on an inbound airplane.

Citation:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Second Lieutenant (Infantry) Samuel F. Telfair, United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with the 2nd Anti-Aircraft Machine Gun Battalion, A.E.F., at Brieulles, France, on 4 November 1918. Second Lieutenant Telfair was leading a patrol to reconnoiter a position for anti-aircraft machine-guns when his group became scattered by intense shell fire. Upon returning to the shell-swept area to look for his patrol, he found one of the men severely wounded. Making two trips through the heavy shell fire he secured the assistance of Private Laurel B. Heath and carried the wounded soldier to safety.

Citation:

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to Sergeant Frank J. Gardella (ASN: 88892), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in action while serving with Machine-Gun Company, 165th Infantry Regiment, 42d Division, A.E.F., north of the River Ourcq, near Villers-sur-Fere, France, 28 July 1918. When two enemy airplanes flew parallel to our Infantry lines north of the River Ourcq, pouring machine-gun bullets into our positions and driving everyone to cover, Sergeant Gardella rushed to his machine gun and took aim at the upper of the two machines. Although he was constantly subject to a storm of bullets from the planes and from enemy snipers on the ground, he nevertheless coolly sighted his gun and riddled the upper plane. It collapsed and fell in flames, striking the lower one as it fell and causing it to crash to the earth also.

The final display reads:

M1918 3-Inch Anti-Aircraft Gun

The M1918 3-Inch Anti-Aircraft Gun represents the culmination of combat experience in the First World War. The US had primarily used foreign-designed heavy guns like the M1897 “French 75” in the heavy gun anti-aircraft role during World War I, with a few M1917 fixed-position 3-inch guns arriving in theater very late in the war.

The Model 1918 3-Inch Anti-Aircraft Gun was the first US-manufactured, purpose-built, mobile anti-aircraft gun. An adaptation of the 3” Coast Artillery Gun, the M1918 had a high muzzle velocity (over 2,400 feet per second) and the new mount allowed for extremely high-angle fire. It completed testing in the Fall of 1918 and the first battery was rushed into service for trials on the Western Front.

Allied observers who viewed the Model 1918 3-Inch Anti-Aircraft Gun were extremely impressed with its performance. British and French efforts in this area were nothing more than mount adaptations of field guns. Those ad-hoc efforts, using weapons that failed to achieve a sufficiently short time of flight, were of limited effectiveness in actually engaging aircraft. The method of engagement had been dubbed “barrage fire” and relied on a wall of shrapnel at a predetermined altitude to deter enemy aircraft rather than precision targeting of individual aircraft. The high-velocity rounds of the M1918 changed that, and although fire control systems were still in their infancy, US anti-aircraft gunners now had a weapon they could use effectively.

There is some question as to whether the M1918 saw combat in World War I. Most sources show that the test guns did not get overseas until December 1918, a month after the Armistice was signed.

The M1918 soldiered on during the interwar years, serving as the primary weapon system for American Coast Artillery Anti-Aircraft units until its replacement, the M3 3-Inch Anti-Aircraft Gun began coming on line in 1928.

The last M1918 guns were phased out of service by 1932. Although production figures are vague, several hundred M1918 Guns were manufactured between 1918 and the early 1920s. Of those hundreds of early AA guns that defended American skies, only one now survives.

The Museum’s M1918 3” Gun was completely restored in 2013 and is as close to its original, operational configuration as possible.

Pointing the M1918 was a complex process, involving two gunners on each side to aim, traverse and elevate the gun.

Unlike earlier weapons that had been pressed into anti-aircraft service, the M1918 had a maximum elevation that was near-vertical, allowing for better target tracking.

Although heavy coastal defense guns were still the focus of the Coast Artillery Corps in the 1920s, anti-aircraft gun emplacements were quickly collocated to defend the heavy guns against potential air attack.

Taken December 13th, 2013.

Image from page 361 of “The origin and history of the primitive Methodist Church” (1880)

Image by Internet Archive Book Images

Identifier: originhistoryofp01kend

Title: The origin and history of the primitive Methodist Church

Year: 1880 (1880s)

Authors: Kendall, H. B

Subjects: Methodist Church — History

Publisher: London : Dalton

Contributing Library: University of California Libraries

Digitizing Sponsor: MSN

View Book Page: Book Viewer

About This Book: Catalog Entry

View All Images: All Images From Book

Click here to view book online to see this illustration in context in a browseable online version of this book.

Text Appearing Before Image:

MITIVE METHODIST CHURCH, * lircuit, and though Nottingham had its Circuit Committee, and Leicestershire was notwithout its capable officials, there was left a gap in discipline which the PreparatoryMeeting of 1819 was intended to supply. As to the separation of R. Winfield,growing out of his refusal to accept his appointment to Hull—that will moreappropriately be dealt with in our next chapter. The retirement of Benton must detain us a little while. Had he died, or emigrated,or seceded, our task would have been a simpler one. But he lived for thirty-eightyears after his retirement; and yet he became in a sense dead to Primitive Methodism.This is the fact that needs explanation. We are not specially prepared for this retire-ment by anything we have met with or observed. We might, possibly, have predictedthe retirement of Crawfoot; scarcely that of Benton. The event comes upon ussomewhat as a surprise, and we are almost ready to bring in the verdict—Silenced bythe visitation of God.

Text Appearing After Image:

Kill M> Illl.L tAMI* MEETING SITE. In the month of .May, 1818,—two months after the opening of Leicester—a greatcamp meeting was held at Round Hill—a popular site for such gatherings. Withcharacteristic precision Hugh Bourne thus describes the position of Round Hill. Iti- an elevated piece of ground, about three and a half miles from Leicester, and issituated at the junction of the Roman Fosse Way with the Melton Turnpike Road.Time and place were favourable for a large gathering; and there was one. From everydirection people came, on fool and in vehicles of all kinds, until it was computed therewere ten thousand persons present. The meeting was well supported by preachers andpraying labourers. The morning service had been powerful, yet marked by decorum.At noon the converting work broke out, and the cries for mercy were loud andcontinuous. Benton was in great force; and as he spoke on the great day of Gods THE PERIOD OF CIRCUIT PREDOMINANCE AND ENTERPRISE. 353 wrath, and the

Note About Images

Please note that these images are extracted from scanned page images that may have been digitally enhanced for readability – coloration and appearance of these illustrations may not perfectly resemble the original work.